Agency of Shifting Uncertain Situations

BETWEEN MAY 9th and JUNE 23rd, 2020—amid the resurgence of demonstrations and uprisings across the United States—a subset of the New Models community held a focused debate around the mechanics and aesthetics of contemporary crowds. What are the truths of crowds both "real" and "fake"? Who and what directs their flows? And what is the cost (and price) for the bodies that show up? Central to this discussion was "astroturfing" (i.e., the manufacturing of "grass roots") and its historical precedents.

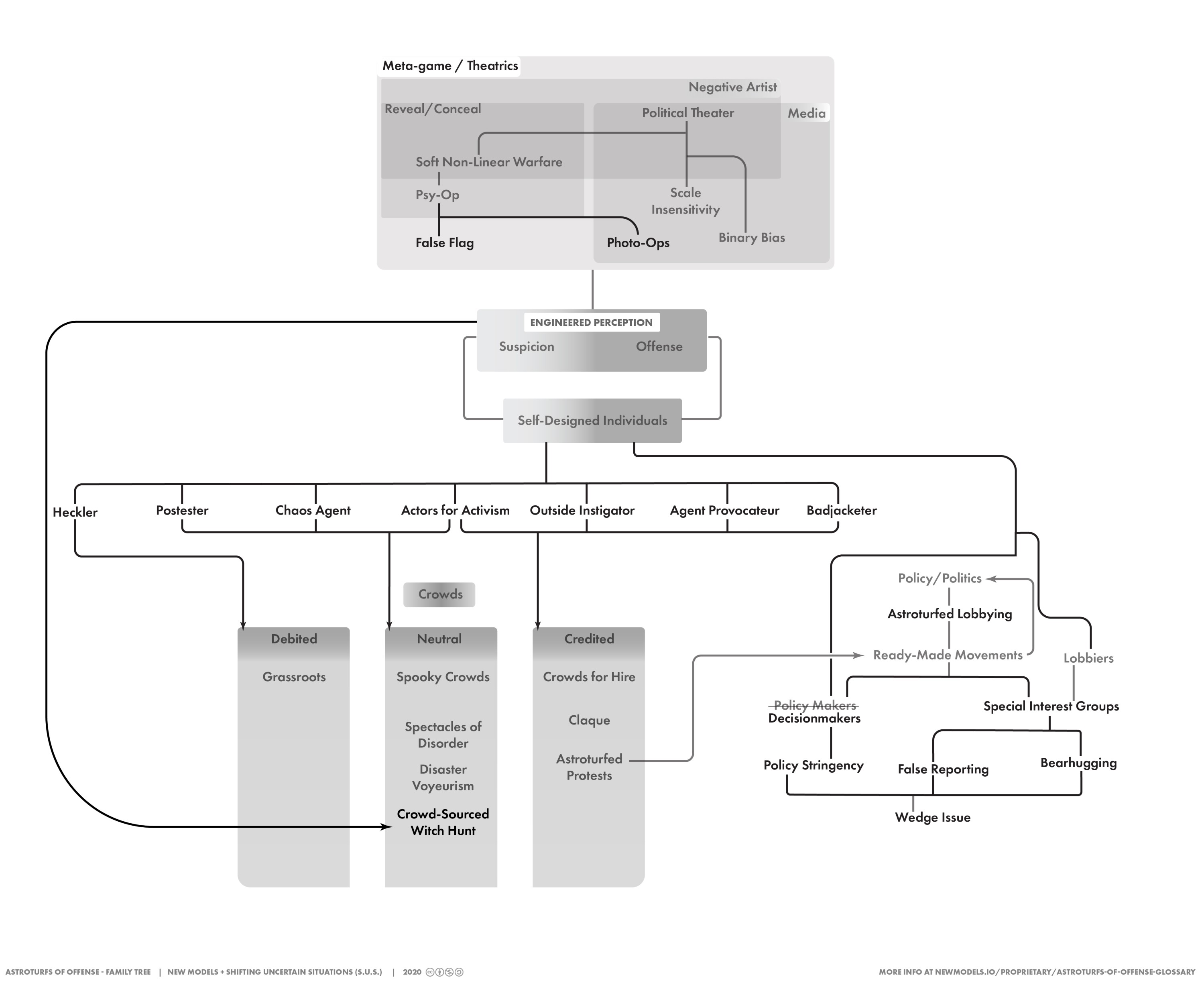

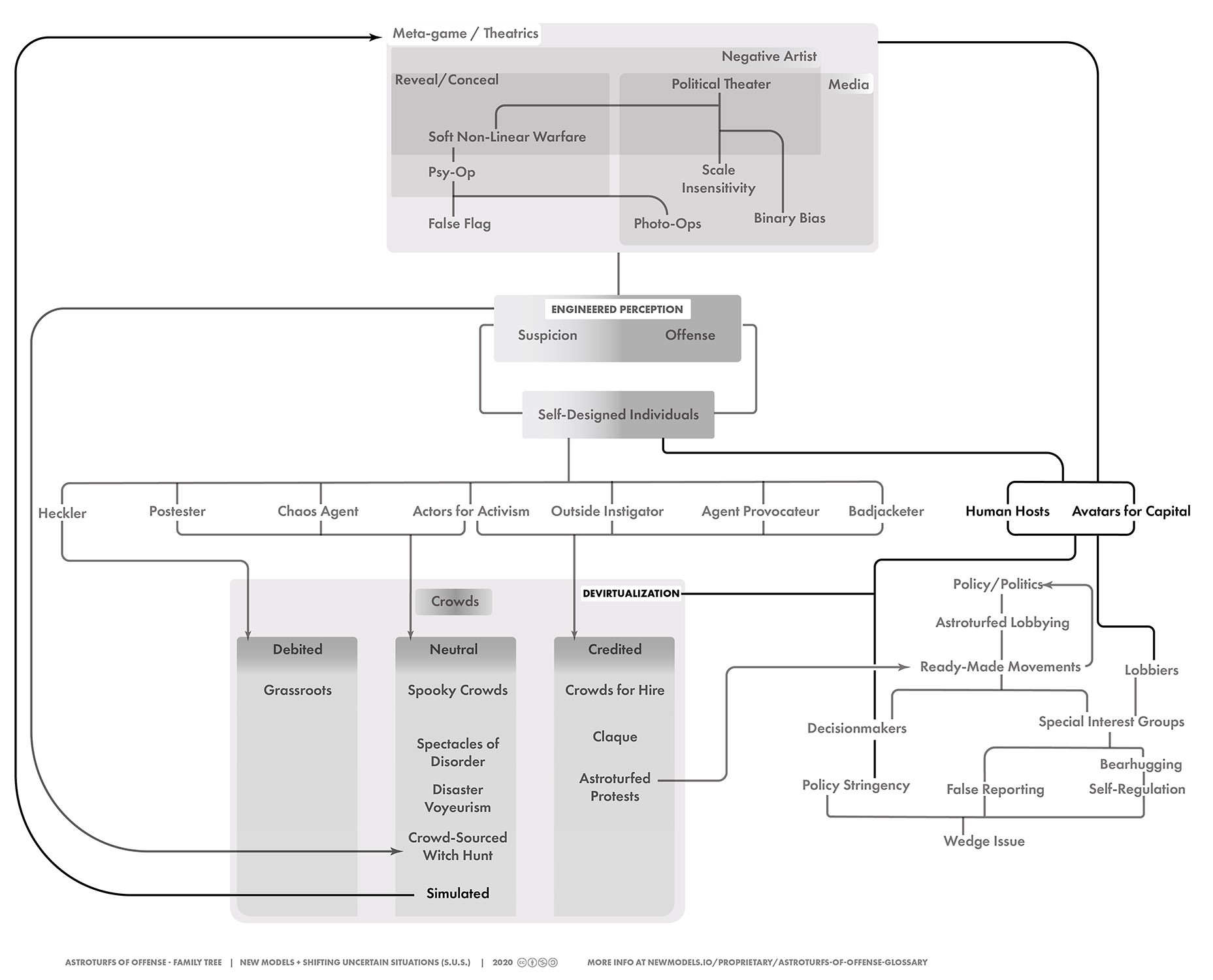

As the year comes to a close, we are publishing a condensed, anonymized version of that conversation here, along with the glossary and diagrams produced by the Agency of Shifting Uncertain Situations or S.U.S. in the wake of this discussion. S.U.S. spokespeople Jak Ritger and Clack Auden also recorded a Special Report with New Models, "Uncanny Rally," where they fleshed out their research—and the agency's mission to sow productive ambiguity in the face of consensus.

On the episode, Ritger and Auden remind us that "astroturfing" and related practices are exclusive to neither the Right nor the Left, and that they are deployed for a range of reasons, defying easy binaries. S.U.S. encourages protest leaders and participants to download their materials for distribution wherever crowds emerge.

Download 📄 A S.U.S. Glossary & Diagram of Astroturfing (2020)

NEW MODELS COMMUNITY DEBATES: ASTROTURFING

@NM1 To lay the ground for this discussion around astroturfing, I offer a summary of artist David Levine's 2018 lecture on the theory and practice of fake crowds. His lecture draws on the history of the claque to make sense of the crowds-for-hire (in contrast to grassroots campaigns) phenomenon that entered mainstream American political discourse around the 2016 US election. Levine poses the question: “Why do we [specifically, Americans] find the idea of fake crowds so viscerally offensive?” He caveats this question by positing that:

2) Americans place a premium of faith in the crowd, even though this faith is at odds with 19th and 20th century discourse around crowds, which skewed toward distrust: fear of both the chaos (unruly mobs) and conformism (loss of individualism) that crowds can engender.

Levine argues that the modern fear is no longer one of crowds so much as the presence of people who haven’t yet surrendered their autonomy to a collective—or rather, those who have but to a collective directed by an outside force whose motivations are not publicly transparent (as in astroturfing). Complicating this is the fact that the people who comprise astroturfing efforts often do hold shared beliefs; what's perceived as egregious is that they are funded by veiled outside sources such as nonprofits or individual wealth.

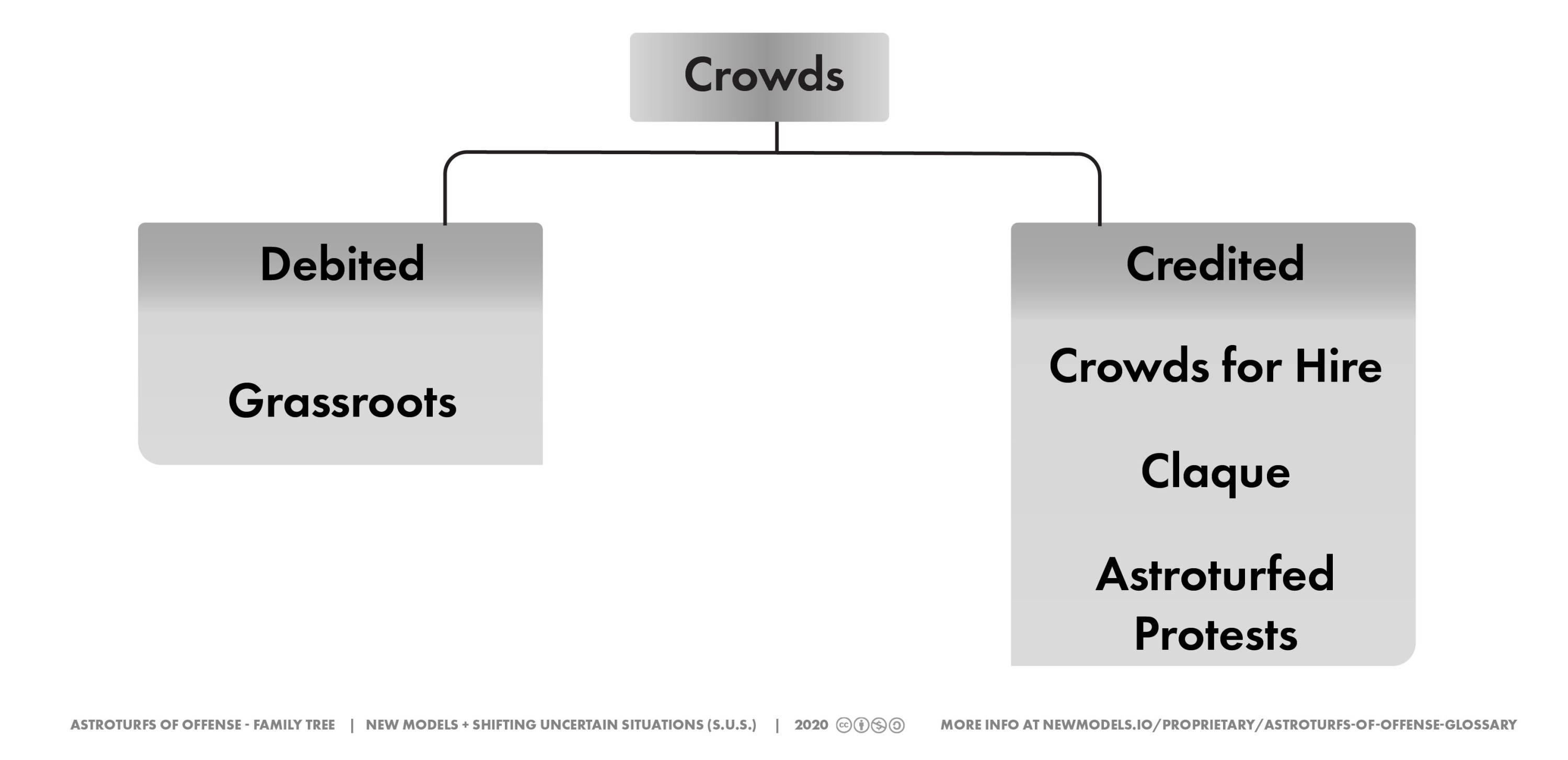

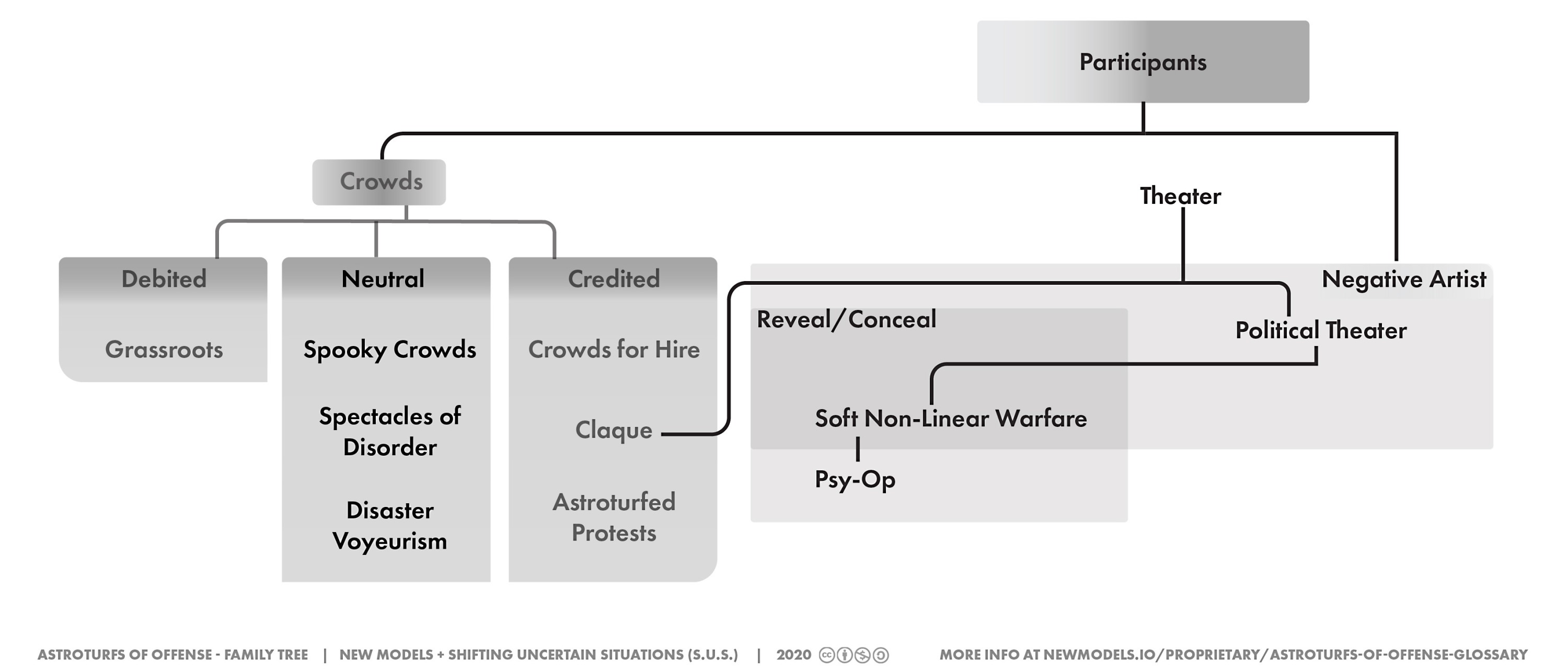

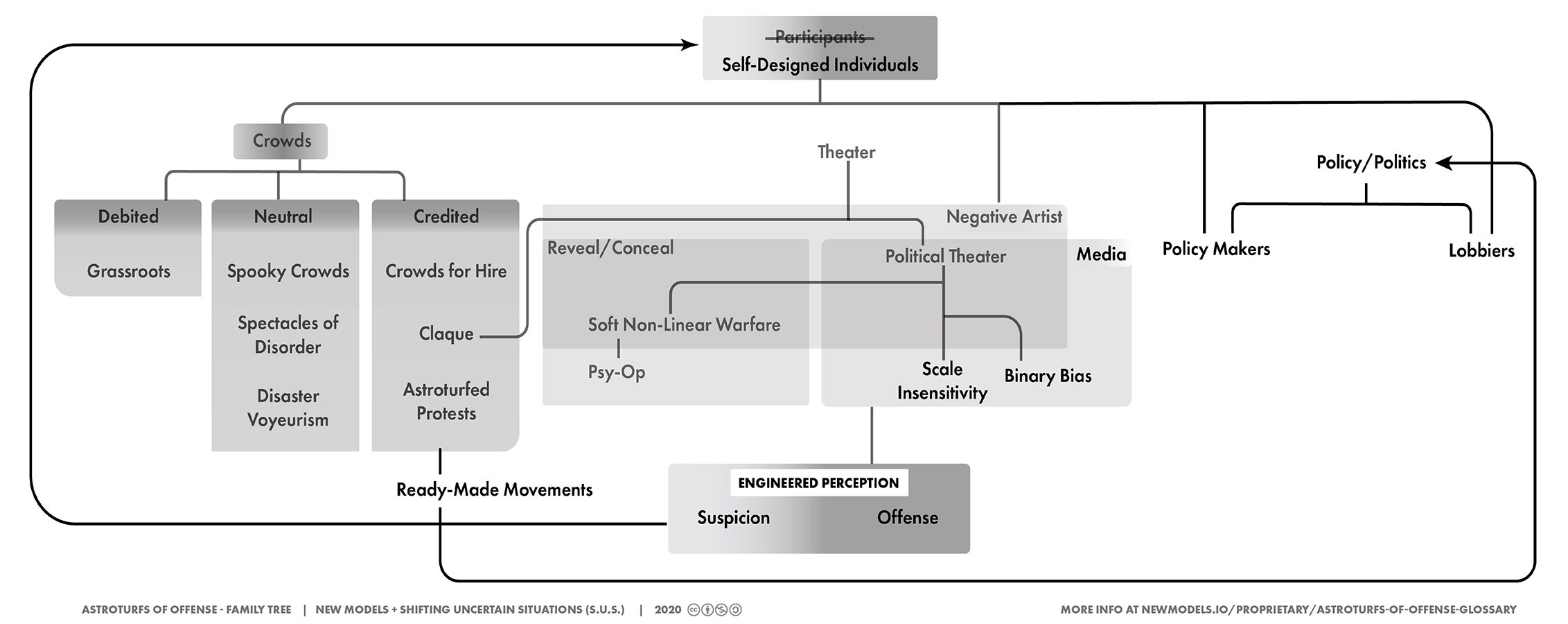

In this economic dynamic, there are credited and debited individuals: those who are credited are ‘paid off immediately,’ whereas those that are debited freely invest their potential labor time in return for potential futures. Credited (astroturfed) crowds are beholden to a type of economic expediency. Though they may share beliefs, they are ultimately serving the interests of those supplying immediate credit. By contrast, debited crowds sacrifice their own time, with no promise of a return on their investment; these individuals are mutually imbricated in their shared struggle and collective indebtedness. Formally: credited crowds are asocial, disinterested, and meaningfully incoherent; debited crowds are social, interested, and meaningfully coherent. Levine recognizes these differences, but posits that aside from disturbing our sensibilities, there is actually little difference in terms of political impact.

@NM3 Vladislav Surkov is an interesting figure to bring into this discussion. He coined the term soft non-linear warfare and is important in understanding the dynamics of political theater. I like the idea of the negative artist from James Dixon's essay "Is Vladislav Surkov and Artist?". It opens up the possibility that not everyone who utilizes art is doing it for egalitarian outcomes. Surkov's strategy is crucial: fund both the opposition and the statist sides of political demonstrations and then reveal that this is what was being done. In turn, no one knows who is "genuine" and who is paid, and thus the default assumption is that everyone is equally corrupted and so no one can be trusted. Adam Curtis outlines this play in the conclusion of his 2016 film HyperNormalisation.

When the liberal media obsessed over Russiagate for three years, taking the relatively small amount of Facebook ads ($500K) that were actually seeded by the Russian psy-op and extrapolating this out to include every single pro-Trump message, they were in effect working the same angle: delegitimizing both the opposition and themselves through a narrative of corruption that effectively 'finished the job' for the Russians.

I really like the bit about Americans being very innocent and scandalized by the proposition of faked crowds. That's something I need to take into consideration when labeling opposing political actions as "astroturfed."

@NM4 Let's add spooky crowds à la Ray Bradbury's “The Crowd" on disaster voyeurism and being drawn to the spectacle of suffering.

@NM1 This feels like a spectacle of disorder, @NM4. The cyclical/consuming quality of the crowd in Bradbury's text connects to the way that discussion around astroturfing almost always falls along ingrained ideological lines. Hopefully this discussion, here, can in part break the cycle.

@NM1 Levine makes an observation in an ep of the Theory of Everything podcast (thanks @NM2) that might help make sense of the media's disproportionate coverage of small-sized demonstrations/protests during the COVID-19 lockdown:

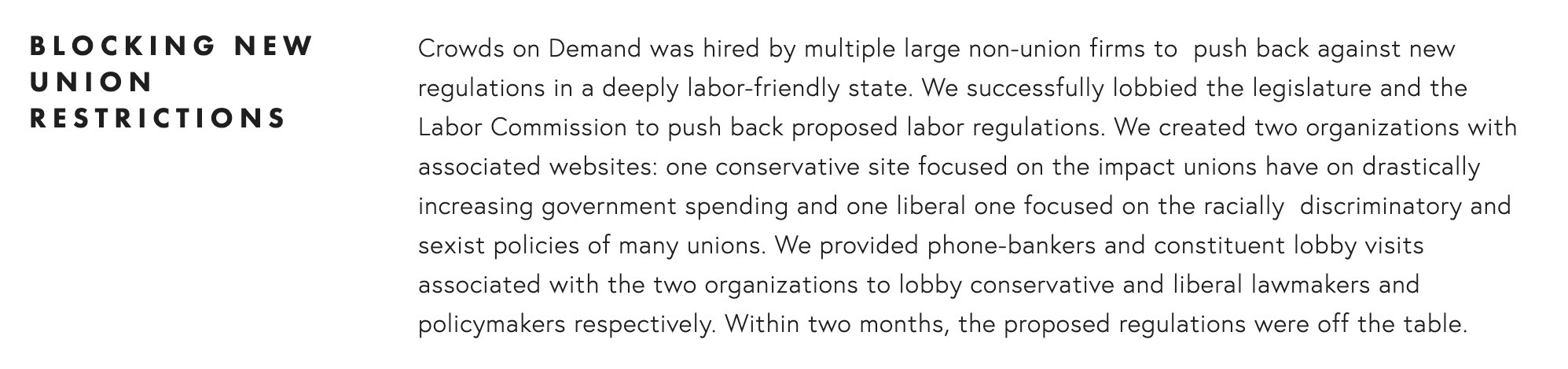

The ‘reveal’ factor that you mention, @NM3, seems critical to understanding and accepting political theater in a Survov-style context. Yet there is still such a big difference in awareness/acceptance between Russia and the US. At the same time, America is not innocent. For instance, this US company Crowds on Demand blatantly markets itself as an "American publicity firm that provides clients with hired actors to pose as fans paparazzi, security guards, unpaid protesters and professional paid protesters" and advertises use-cases such as:

I was struck by the section on self-design in Dixon's Surkov essay—particularly these excerpts on the feelings of suspicion and offense towards fake crowds:

"As we no longer believe in the purity and sincerity of the Modernist white cube we seek the cracks to satisfy our cynicism, only when we feel we have seen beneath the surface, and glimpsed the ugly truth is our faith restored."

Regarding negative artists: One reference point is Claire Bishop’s Artificial Hells (2012)—chapter 8 in particular, “Delegated Performance: Outsourcing Authenticity.”

@NM5 I’ve ranted on about scope insensitivity elsewhere but it's also relevant here as it's something that the media so often exploits as a way of controlling and direction attention. A protest of 100 people demanding to "re-open America" so they can return to work is suddenly all over the national news and we start to think everyone who isn't "us" must be a specific "them" that is in agreement with these protesters. Scope Insensitivity + Binary Bias + Mass Media = SIMPLE engineering of people's perception / organization of society AT LARGE.

@NM6 What about the political power of the anti-vaxxers? It looks like only 64% of Americans (out of 2000 polled) are a for-sure "yes" for a Covid-19 vaccination. I assumed it would've been higher. Isn't there a danger of anti-vaxxers and libertarians coming together, like the Christian and Evangelical right in the '70s, and being enough to sway an election? In Canada, 28% object to a mandatory Covid-19 vaccination. Where I am, the anti-vaxxers seem to be sincere and rich and not putting on an act—at least not to my knowledge. But thinking of that movement being united by astroturfing, you can imagine it being turned into something with broader, tighter affinities. Through the Surkov lens, what could this do if needed? There could be some strategy of having lots of irons in the fire, and then strategically picking up the ones you need. The anti-vax group seems like a ripe catalyst with serious weight.

@NM1 Makes me think of astroturfs as a model or template (boilerplate) for aligning or combining any ready-made movement. A kind of at-the-ready default form of protest—a defaultism.

@NM3 Regarding @NM1's question about how US and Russian awareness/acceptance of astroturfing differs (Crowds on Demand as an industry secret vs. Surkov revealing that both sides of a wedge issue have been astroturfed): In Russia, the government treats protest movements like chess pieces in a longer meta-game of sowing disillusionment about confronting power. CrowdsOD is more about achieving specific, short-term political goals. The 'reveal factor' in the US is more decentralized and operationalized by each and every political actor—"The Tea-Party is astroturfed" / "Occupy is funded by Soros"—instead of a central figure like Surkov making it known that he has masterminded everything.

This framing might be useful for countering the anti-lockdown protests. It is ineffective to simply say "they are funded by Betsy Devos or landscaping companies." This line of attack is used by both sides all the time, in good and bad faith. But who funds the astroturfing is inconsequential. Also, if someone does agree with the anti-lockdown folks, this will only make them dig in harder as it comes off as dismissive. A better tactic might be to point to @NM5's scale-jumping framing: this is 100 people, they do not speak for the vast numbers of people supportive of lockdown/vaccines.

Thinking about the media's role in all this, I watched the 1969 film Medium Cool, which follows a news cameraman as he goes from emotionless ambulance chaser, to civil rights activist. The film's narrative plays out in front of real activist marches / police attacks. Two moments jumped out:

Today the relationship between media and protests is stronger than ever. In turn, astroturfing is less about actual bodies in space and more about staging photo-ops for media, a kind of backfilling with CrowdsOD actors for activism.

I also came across an interview with Clemens von Wedemeyer, an artist whose work involves simulating crowds and crowd dynamics. "Humans are defined by their relationships." This got me thinking: Abstraction evolves from the fact that large companies and states can get useful information through [anonymized] behavior patterns. There's often no need to examine the individual or individual psychology; only how or with whom the individual is acting. When something doesn't fit into a learned pattern, that's when the alarm system goes off.

Political motives are not considered, only numbers and connections. This prioritizing quantitative over qualitative engagement really makes it seem like the astroturfers will have an upper hand in the future. Maybe there is need to devise a new model for protest that can bring it back to the qualitative?

@NM1 Wedemeyer makes reference to Elias Canetti's 1960 book Crowds and Power (Masse und Macht) as source material for modeling crowds. Will be checking it out.

@NM7 There may be possible overlap here with the figure of the heckler. Writer Huw Lemmey recently published a piece exploring the history of the heckler in English politics in particular, and the way that the perception of the heckler as a democratic/anti-democratic force has changed over time.

@NM8 Somewhere in the family tree of astroturfing are the agent provocateur, the false flag, the outside instigator, the chaos agent, and the crowd-sourced witch hunt.

@NM9 As well as the badjacketer.

@NM3 "Badjacketing" spoke to my initial reaction of the video of the umbrella guy from the Minnesota uprising, which was: yeah he looks very sus, but it's beside the point whether or not he’s actually a cop. Trying to frame riot as the result of one person's actions serves this model protester, and undermines the uprising.

@NM1 Came across a 2002 article by Thomas P. Lyon and John W. Maxwell titled "Astroturf Lobbying." In it, Lyon and Maxwell build off a Simple Model of Lobbying, which presents a formal equilibrium between decision-makers and special interest groups. Their article is also useful for explaining the term bearhug and understanding policy in terms of stringency.

@NM3 News today: Actors playing black panthers, showing up with guns, then linking arms with cops in Atlanta. I highly doubt this is some sort of astroturf. More likely just actors showing up causing a scene, 'doing it for the gram.' Perhaps it’s better to view this as protesting + social media = highly charged visuals with low-res politics—maybe a postester.

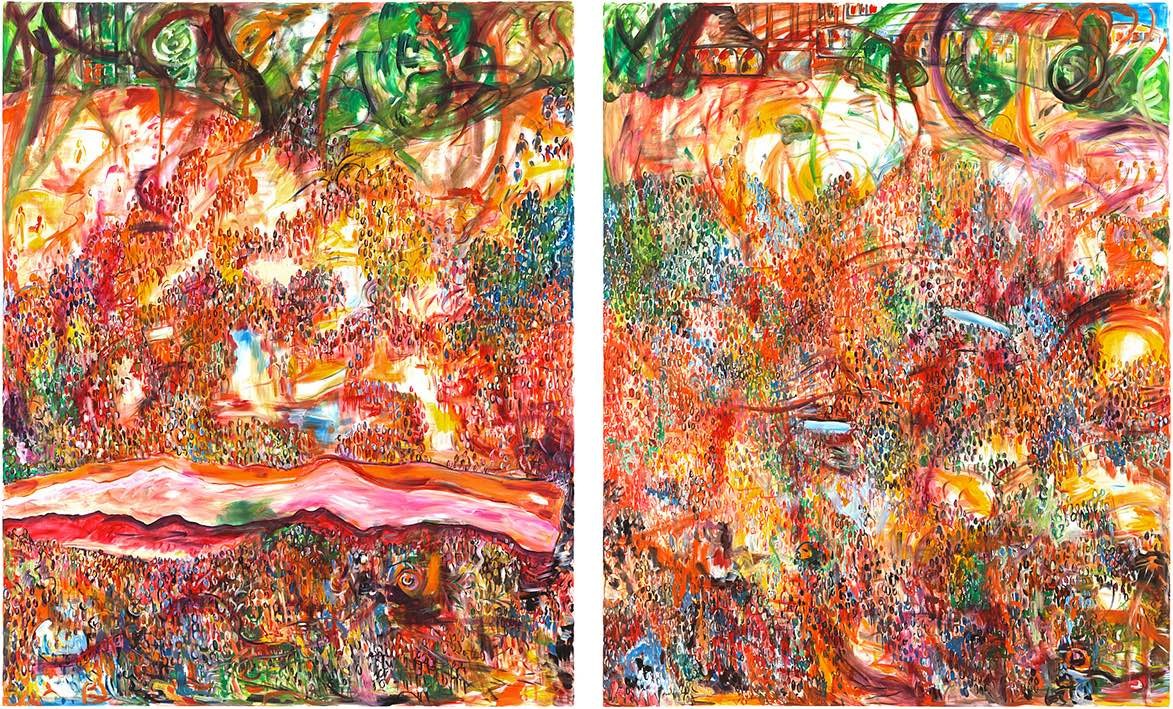

@NM1 Am reading Canetti's Crowds and Power and watched von Wedemeyer's 70.001. Early in the book, Canetti observes that "as soon as [the crowd] exists at all, it wants to consist of more people: the urge to grow is the first and supreme attribute of the crowd." He goes on to write that "the open crowd exists so long as it grows; it disintegrates as soon as it stops growing."

70.001 takes those axioms to logical conclusions. In the video work, the crowd continues to grow in size, listlessly moving through an accelerated time-lapse of day and night, never sleeping or needing of any particular human desire (except for the crowd to grow larger). Scenes are completely frictionless in terms of the interactions among individuals and between the crowd and its surrounding environment. Though at one point there is evidence of what Canetti describes as the "potential destructiveness of the crowd" (an inevitability of massive growth in any given environment...). In von Wedemeyer's work, the crowd's growth is continuous yet it's integrity/power is compromised at the end of the piece when camera zooms into the mass clearly revealing the repetition and interchangeability of the crowd's computer generated individuals.

What I find interesting about the piece is the way that it works with crowds at the formal level, extrapolating Canetti's vignettes of the crowd and their topologies of gestures into what Levine might recognize as purely disinterested actors (here the digital, interchangeable sprites/assets/avatars).

@NM3 The idea of a crowd as a sentient being—wishing to constantly grow and starting to disintegrate when it stops growing—makes me think of how capitalism is thought of now, as an entity in and of itself. @NM5 once described global capitalism today as a kind of A.I.: operating off unknowable algorithms making split second trades, human hosts (CEOs) acting as avatars for capital.

This idea of constant growth, simulacra, crowd simulation makes me think of a Paul Bush film I saw a couple years ago called Babledom (2012). It is an experimental narrative about a city that grows so fast that no one alive has ever stepped on the ground or seen the sky. All the images in the film are from research departments simulating human movement and crowd behavior.

In thinking about astroturfing, these studies (meditations on simulated crowds and crowd behavior) feel like an inversion of the relationship to power. Meaning, the IRL astroturfed crowds can be understood as a devirtualization of simulated realities, where capital/corporate interests are a stand in for computer systems.

DOWNLOAD 📄: A S.U.S. Glossary & Diagram of Astroturfing (2020)

FOR MORE

https://clack.life/ & https://www.punctr.art/

To join the New Models Discord, subscribe at: https://patreon.com/newmodels